Perceptron Playground — When It Works and When It Fails

Today, I took a step back to explore one of the most classic algorithms in machine learning: the Perceptron.

It’s simple, lightning-fast to train, and a great first stop for anyone trying to understand how linear models work.

But — as I quickly learned — it’s also the perfect example of why we sometimes need more than just a straight line.

What is a Perceptron? Think of it as a single neuron in a brain-inspired network: it takes in input features → multiplies them by weights → adds a bias → and runs the sum through a step function to decide between two classes.

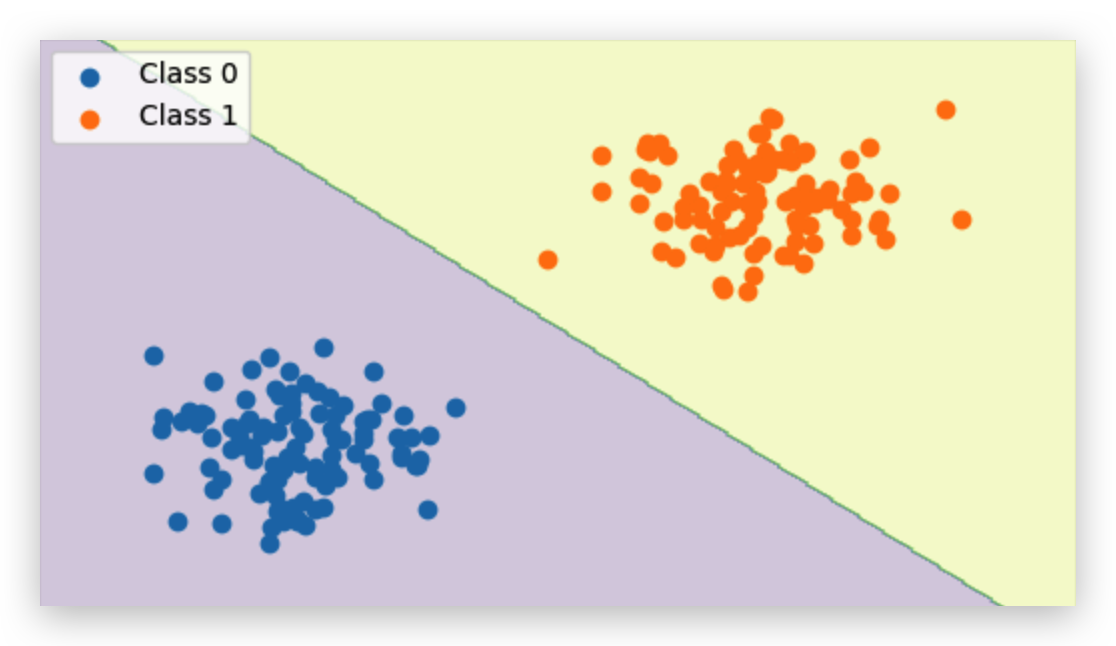

Linearly Separable Data — The Perceptron’s Comfort Zone

To warm up, I generated two Gaussian blobs that can be perfectly split by a straight line.

Here’s what happened when I trained a perceptron:

When I trained the perceptron on this perfectly separable dataset, it almost felt too easy — the algorithm just kept adjusting the weights until it found the exact straight line that separated the two groups. Once that line was found, it stopped making updates, because every single point was classified correctly. On the plot, you can see a clear boundary running right between the blobs with no mistakes at all. This is the perceptron in its happy place.

If your dataset can be split perfectly by a straight line, a perceptron will find that line and stop updating its weights once all points are correctly classified

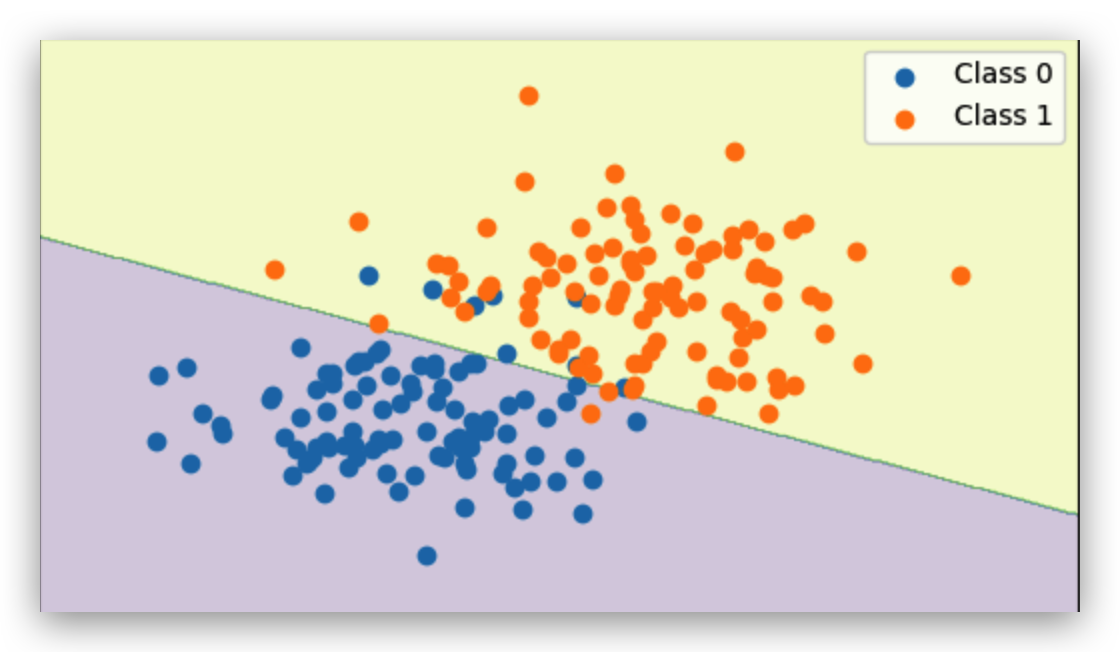

Partial Overlap — Imperfect but Still Linear

I then moved the blobs closer together, creating some overlap.

When I moved the blobs closer, things got trickier. The perceptron still tried its best to find a straight line, but now some points from different classes were mixed together in the same space. No matter how the line was drawn, a few points were always on the wrong side. You can actually see this in the plot — the boundary runs in the middle, but there are little “intruders” in both regions. This is a limitation of any model that’s only allowed to draw a straight line: it simply can’t separate overlapping data perfectly.

Don’t expect 100% accuracy if your classes overlap — no matter how long you train, a linear model can’t do magic here.

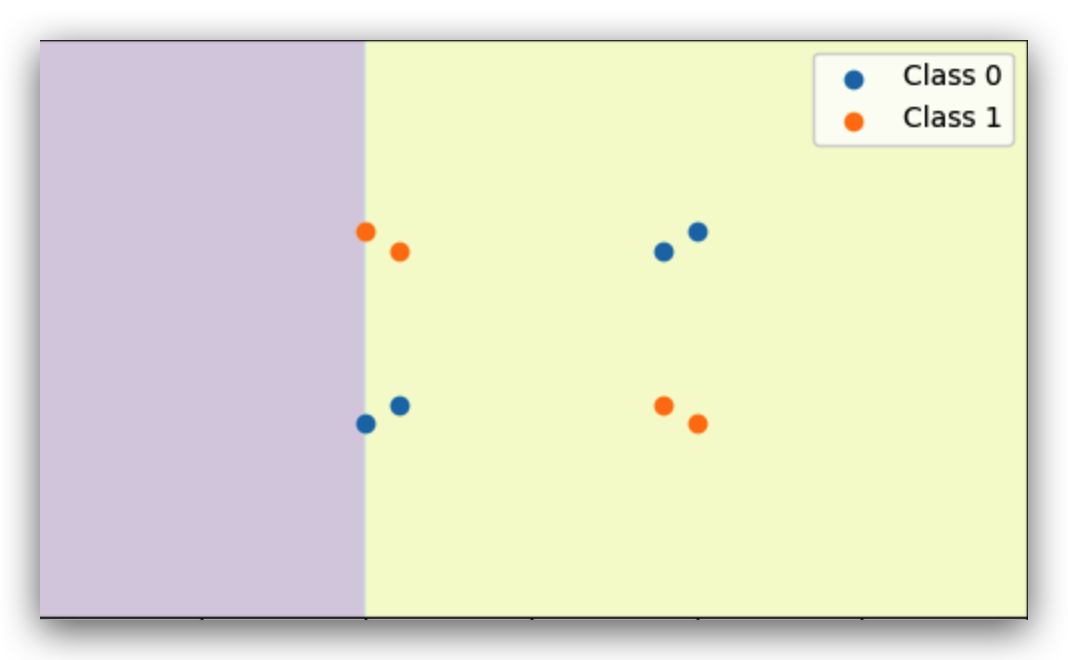

The Famous XOR Problem — A Hard Fail

The XOR dataset labels alternate corners differently.

No single straight line can separate these points.

The XOR dataset is like a trick question for the perceptron. The points are arranged so that opposite corners belong to the same class. I trained the perceptron for many iterations, but it kept “guessing” wrong half the time. The reason is simple: there’s no single straight line that can separate these points correctly. If you draw a line to fix one part, you immediately mess up another. This is a classic example in ML theory that shows why the perceptron needs something more — like hidden layers — to handle non-linear patterns.

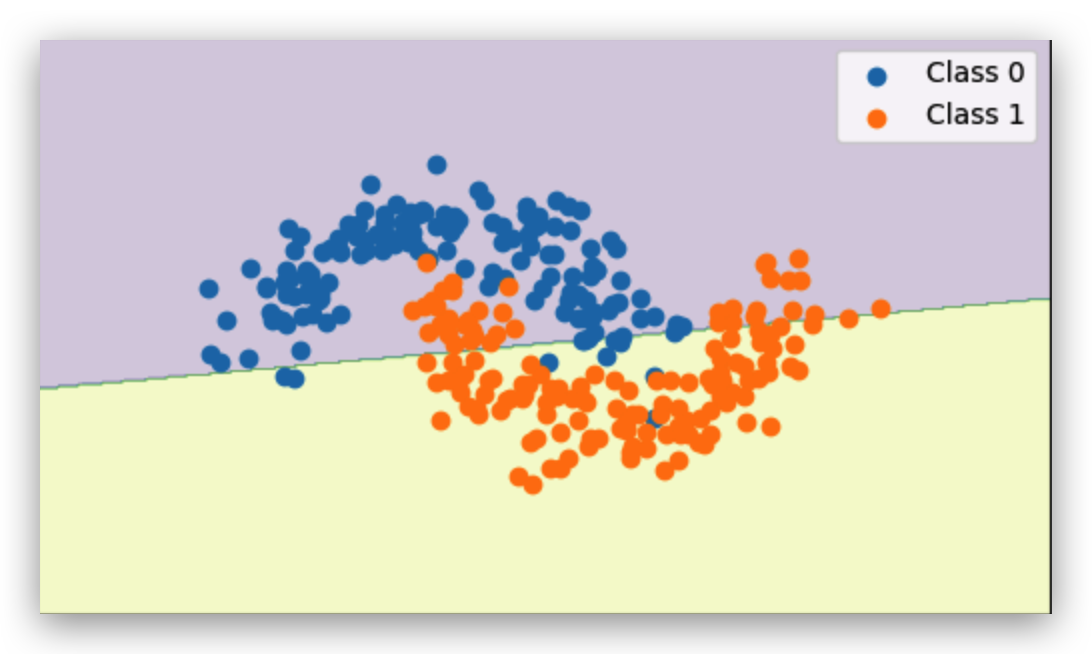

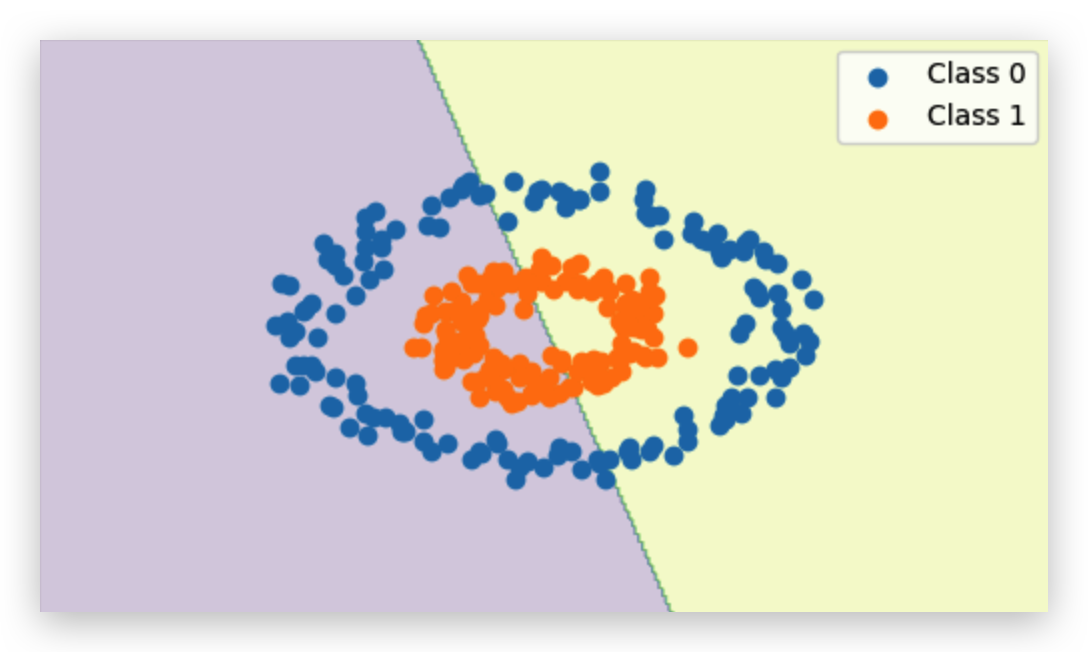

Curved Boundaries — Moons and Circles

I also tried datasets where the boundary is curved:

- Two Moons: Interleaved crescents.

- Concentric Circles: Inner ring vs outer ring.

When I tested the perceptron on datasets with curved shapes, like the “two moons” or “concentric circles,” the mismatch was obvious. The model can only draw a flat line, but the true dividing line is curved. On the plots, you can see the perceptron’s line slicing awkwardly through both shapes, misclassifying big chunks of points. This isn’t a training issue — it’s a geometry problem. The perceptron’s “mental model” of the world is flat, so anything that requires bending or wrapping around data points is beyond its reach.

Summary — Key Takeaways

- Perceptrons work well only for linearly separable binary classification.

- Overlapping or non-linear patterns require either:

- Feature transformations (e.g., polynomial features)

- Multi-layer networks (MLPs) with non-linear activations

- The XOR problem is the classic proof that we need hidden layers.

This is exactly why modern deep learning architectures stack multiple layers with non-linearities — so they can model boundaries of any shape, not just straight lines.

What’s Next?

In the next post, I’ll explore some other new learnings — building on today’s perceptron insights and diving deeper into my ML/DL journey.

Full notebook: Perceptron Playground on GitHub